Corruption in small businesses is not a myth—it's a significant and often underestimated threat. Organizations lose approximately 5% of their annual revenue to fraud worldwide, and this figure impacts businesses of all sizes. What distinguishes fraud in small enterprises is its devastating relative impact: a $100,000 fraud loss that a corporation might absorb represents an existential threat to many small businesses. The compounding challenge is that smaller organizations often lack the sophisticated oversight systems, dedicated compliance personnel, and financial resources that characterize larger corporations.

Yet the good news is equally compelling: corruption prevention in resource-constrained environments is not only possible—it is highly achievable with disciplined implementation of proven, affordable strategies. This article provides a framework that business owners and managers can implement immediately, regardless of team size or budget limitations.

Understanding the Corruption Landscape in Small Businesses

Before designing prevention systems, it is essential to understand how corruption manifests in small operations. Research identifies four primary categories of business corruption, each with distinct characteristics and detection challenges.

Asset Misappropriation represents the most prevalent form of corruption in small businesses, accounting for 86% of all occupational fraud cases with a median loss of $100,000 per incident. This category encompasses several distinct schemes: skimming (removing cash before it is recorded), larceny (stealing cash that has already been recorded), and fraudulent disbursements (issuing unauthorized payments). These schemes are particularly difficult to detect in small organizations because limited staffing often means that the same employee handles multiple stages of financial transactions.

Bribery and Kickbacks occur when employees or vendors offer or accept payments in exchange for preferential treatment. Unlike asset misappropriation, bribery is often disguised as legitimate business activity and may involve external parties, making it harder to identify through internal controls alone. A procurement officer may accept a payment from a supplier in exchange for awarding contracts at inflated prices, or a manager may accept gifts for approving vendor relationships.

Financial Statement Fraud involves the intentional manipulation of financial records to present a falsely favorable picture of the company's financial position. This might include overstating revenues, understating liabilities, or failing to disclose material information. While less common than asset misappropriation, financial statement fraud typically causes more substantial damage when discovered.

Embezzlement and Conflict of Interest represent the final major category. Embezzlement occurs when individuals with access to company funds misappropriate them for personal use. Conflicts of interest arise when employees prioritize personal financial gain over their duties to the company—for example, hiring relatives despite company policy or manipulating procurement decisions to benefit personal relationships.

Small businesses are disproportionately vulnerable to these forms of corruption for several structural reasons. Limited staff creates overlapping responsibilities, making it difficult to maintain segregation of duties. High-trust environments, often characteristic of small organizations where employees have personal relationships with leadership, can paradoxically create conditions for fraud because informal controls replace formal oversight. Additionally, constrained budgets typically mean that small businesses lack dedicated compliance personnel, forensic accounting capabilities, or advanced fraud detection technologies.

The Cost-Benefit Argument: Why Prevention Pays

Business owners often defer corruption prevention investments, viewing them as expenses that divert resources from revenue-generating activities. This perspective fundamentally misses the economics of fraud prevention. Consider the mathematics: the average fraud loss in small organizations reaches $145,000 per incident. A comprehensive whistleblower hotline for a small organization typically costs less than $1,000 annually—often as little as $29 to $99 per month. This means that preventing even a single incident pays for the prevention system many times over.

Moreover, prevention is substantially more cost-effective than remediation. The cost of a fraud investigation, legal proceedings, reputational damage, and operational disruption far exceeds the cost of preventive measures. Research demonstrates that organizations implementing fraud awareness programs and anonymous reporting mechanisms experience fraud losses 50% lower than comparable organizations without such programs. For a small business operating on thin margins, this 50% reduction in fraud losses can determine whether the company survives a crisis or collapses.

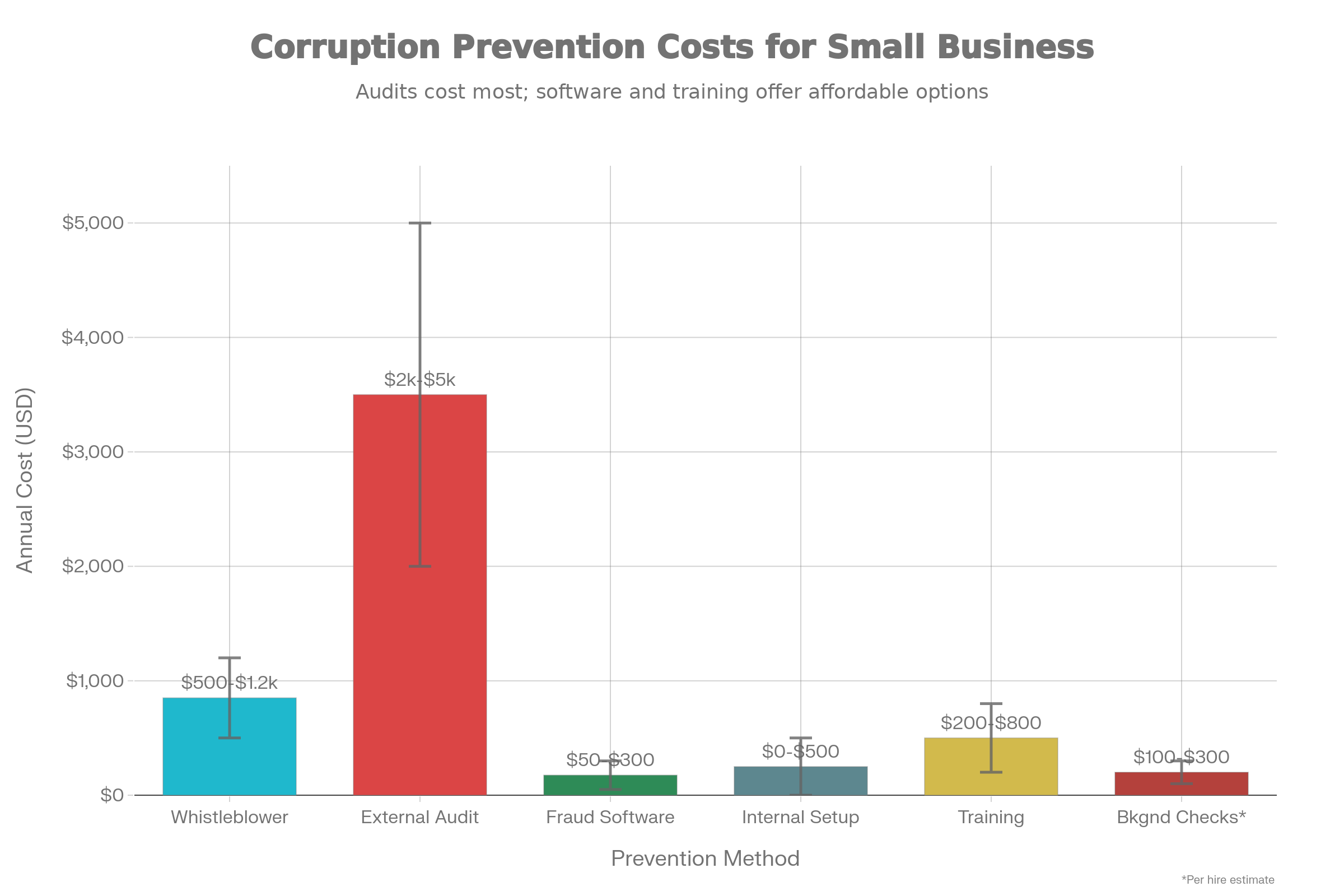

Chart: Annual Costs of Corruption Prevention Measures for Small Businesses

Building a Prevention Framework: The Control Environment

The foundation of corruption prevention is not technology or sophisticated audit procedures—it is culture. Research consistently demonstrates that organizations with strong ethical cultures experience significantly lower fraud rates. Companies that clearly articulate zero-tolerance policies for corruption, where leadership visibly models integrity, and where employees understand the company's values and behavioral expectations experience substantially fewer incidents.

Creating this ethical foundation requires explicit commitment from ownership and senior management. The "tone at the top" is not merely corporate rhetoric; it is a measurable determinant of organizational integrity. Leaders must clearly communicate that corruption will not be tolerated, that integrity is non-negotiable, and that ethical behavior is expected across all levels and situations. Importantly, this commitment must be consistent: if leaders engage in minor ethical compromises or permit politically connected employees to circumvent rules, employees will recognize the hypocrisy and calibrate their own ethical standards accordingly.

Small business owners have a structural advantage in this regard. The personal relationships and direct communication channels that characterize small enterprises allow owners to model integrity visibly and frequently. Conversely, this same advantage creates vulnerability: if the owner engages in corrupt practices or tolerates them among trusted employees, the organization's ethical culture deteriorates rapidly.

Implementing an ethical control environment also requires clear articulation of expected behavior. A written anti-fraud and anti-corruption policy, even brief, communicates seriousness and provides guidance to employees about what constitutes unacceptable behavior. This policy should include specific examples of prohibited conduct (embezzlement, bribery, falsification of documents), consequences for violations, and reporting procedures.

Practical Prevention Strategy #1: Segregation of Duties with Compensating Controls

Segregation of duties is a foundational principle of internal control: no single employee should have complete control over any critical business process. The classic example involves financial transactions: ideally, the person requesting a purchase should not approve it, the approver should not record the transaction, and a different individual should conduct the reconciliation that verifies the accuracy of the recorded transaction. This structure prevents any single employee from initiating, approving, recording, and concealing fraudulent activity without accomplice collaboration.

The challenge in small organizations is apparent: with five to ten employees, dedicating separate individuals to each step of a process becomes economically impossible. The solution involves implementing "compensating controls"—alternative safeguards that achieve similar protective objectives when traditional segregation cannot be maintained.

Practical compensating controls for small businesses include:

The approval requirement compensating control requires that transactions initiated by one employee be approved by a supervisor or manager before execution. While the initial requester is the same individual in both the request and recording steps, the supervisor's independent approval introduces a check. This requires minimal cost (simply establishing the procedure) and is feasible even in organizations with only two to three employees.

Managerial review and monitoring provides another powerful compensating control. The owner or manager regularly (weekly or monthly, depending on transaction volume) reviews detailed transaction lists, bank statements, and vendor records to identify anomalies. This high-frequency review acts as a detective control—it may not prevent fraud in real-time, but frequent auditing dramatically reduces the duration and magnitude of fraud schemes.

Mandatory vacation policies represent a surprisingly effective control. When employees with financial access must take consecutive vacation weeks during which others handle their responsibilities, fraud schemes are often detected. An employee embezzling funds cannot redirect payments or conceal discrepancies for extended periods while absent, and covering employees often discover irregularities that permanent oversight missed.

Rotation of duties, where employees periodically exchange responsibilities, creates similar effects. When the person who normally approves invoices spends a month reconciling bank statements, they gain visibility into transactions they previously only authorized, potentially revealing fraud patterns.

Joint authorization for high-value transactions requires that purchases above a certain threshold (e.g., $500 or $1,000, depending on business size) require approval from two independent individuals. This does not require segregating the entire payment process—only high-risk transactions—making it practical for small organizations.

The implementation of compensating controls requires only documentation and discipline: creating a written segregation of duties matrix that identifies key transaction types, listing which employees have access to which steps, and documenting how gaps are mitigated through compensating controls. This matrix costs nothing to create, takes a few hours to document, and provides clarity to both management and employees.

Practical Prevention Strategy #2: Regular Audits—Tailored to Small Business Budgets

Audit frequency and depth must be calibrated to business risk and resources. For small businesses, the conventional wisdom—that annual audits are sufficient—should be reconsidered. However, even more frequent comprehensive external audits are affordable.

An annual external audit of financial statements costs between $2,000 and $5,000 for a small business. This investment provides multiple benefits: an independent assessment of financial accuracy, detection of unusual transactions or patterns, and credibility with lenders or potential investors. The independent auditor's perspective often identifies fraud schemes that internal management missed.

Internal audits conducted quarterly or semi-annually by management are virtually free and highly effective. These involve a designated manager—often the owner or a senior employee—systematically reviewing high-risk transactions, testing a sample of financial records, and reconciling accounts. While less rigorous than external audits, frequent internal audits detect anomalies and communicate to employees that financial activity is being monitored. Research shows that organizations with established auditing practices report 30% fewer fraud incidents than those without audits.

Surprise audits are disproportionately effective at deterring and detecting fraud. Unlike scheduled annual audits that employees anticipate, surprise audits eliminate the opportunity for fraudsters to conceal misconduct before auditors arrive. A surprise inventory count, unexpected reconciliation of vendor payments, or sudden review of expense reimbursements often uncover schemes that routine auditing misses. Implementing surprise audits requires no additional cost—only management discipline to execute them unpredictably.

The practical approach for resource-constrained small businesses is a tiered audit strategy: conduct an external financial statement audit annually (cost: $2,000-5,000), supplement this with quarterly internal reviews of high-risk areas (cost: management time), and conduct surprise audits of critical processes such as cash handling or inventory twice yearly (cost: negligible). This combination provides continuous monitoring, maintains independence through external audits, and achieves fraud detection at minimal cost.

Practical Prevention Strategy #3: Implementing a Whistleblower Hotline

Perhaps surprisingly, the most cost-effective fraud detection mechanism available to small businesses is the whistleblower hotline—the mechanism through which employees report misconduct anonymously. This statement requires context because many small business owners assume that their personal relationships with employees eliminate the need for formal reporting channels. In reality, these relationships often prevent reporting.

Employees often hesitate to report suspected fraud or corruption through direct channels because of fear of retaliation, concern about damaging personal relationships, worry that their report will be mishandled or ignored, or fear that management is complicit in the misconduct. An independent hotline removes these barriers: reporting is truly anonymous, the recipient is a neutral third party with no prior relationship to the accused, and the report enters a formal documentation process that creates accountability.

The statistical evidence is compelling: organizations with whistleblower programs experience significantly lower fraud losses than those without. In organizations with robust whistleblower programs and anonymous reporting mechanisms, fraud losses are reduced by nearly 50% compared to organizations without such programs. Moreover, employee tips represent the highest-frequency method of fraud detection, suggesting that employees are acutely aware of misconduct but require a safe channel to report it.

Affordability dispels the primary objection to hotlines in small organizations: Modern providers offer cost-effective solutions specifically designed for small organizations, with pricing starting at $29 per month ($348 annually) and scaling up to approximately $1,000 annually for organizations with 50+ employees. For a small business with 10-20 employees, a comprehensive whistleblower hotline typically costs $500-800 per year—less than five percent of the median fraud loss.

When selecting a hotline provider, small business owners should prioritize several features: true anonymity (callers provide no identifying information), 24/7 accessibility (employees can report during any hour), multi-channel reporting (phone, web, email options for employee convenience), case management functionality (the ability to document, track, and follow up on reports), and secure data handling. Reputable providers ensure that the hotline maintains independence—the service provider, not the business, receives initial reports, ensuring that even leadership cannot identify the caller.

The implementation process is straightforward: select a provider, establish a hotline number and web portal, communicate the hotline's availability and process to employees, and assign an internal point person to receive reports from the hotline provider. Many providers assist with employee communication, offering templates, posters, and training materials that help businesses roll out their hotline effectively.

Practical Prevention Strategy #4: Employee Training and Fraud Awareness

Employee awareness programs represent another low-cost, high-impact prevention mechanism. Research demonstrates that companies implementing regular fraud awareness training experience up to 50% lower median fraud losses. The mechanism is straightforward: employees educated about fraud tactics, risks, and reporting procedures are more likely to recognize suspicious behavior and more willing to report it.

For small businesses, fraud awareness training need not be elaborate. Effective approaches include:

Annual training sessions where a manager or external facilitator explains common fraud schemes, warning signs to watch for, and the reporting process. These sessions require two to three hours annually and cost nothing if conducted internally. External trainers may charge $500-1,500 for a session, but many insurance providers or business associations offer free or low-cost training modules.

Quarterly reminders through email, staff meetings, or bulletin boards keep fraud awareness salient. A brief mention of red flags—unexplained accounting discrepancies, employee reluctance to take vacation, unusual vendor payments—reinforces the message that fraud prevention is a shared responsibility.

Scenario-based training where employees discuss what they would do if they observed suspicious behavior is particularly effective. Real examples from the business or industry make the training relevant and concrete rather than abstract.

A critical component of fraud awareness training is clearly explaining the reporting process and assuring employees that reporting suspected misconduct will not result in retaliation. Many employees remain silent about suspected fraud not because they tolerate it but because they fear the professional consequences of reporting. Explicitly stating that retaliation is prohibited and that confidentiality will be maintained removes this barrier.

Practical Prevention Strategy #5: Monitoring Red Flags and High-Risk Transactions

Corruption leaves traces—patterns in financial records, behavioral changes in employees, and anomalies in transactions. Implementing systematic monitoring of red flags provides early warning and can halt fraud schemes before they cause substantial damage.

Accounting red flags that managers should monitor include unexplained discrepancies between recorded transactions and supporting documentation, unusual revenue patterns (sudden revenue spikes without corresponding increases in cash flow or customer base), inconsistent expense reporting that deviates from historical patterns, and irregular journal entries made outside normal accounting periods. Accounts receivable and payable anomalies are particularly important: duplicate payments to vendors, payments to newly established vendors without supporting documentation, or significant adjustments to customer accounts should trigger investigation.

Payroll red flags include ghost employees (names appearing on payroll records without corresponding timesheet documentation), unauthorized rate changes (employees receiving raises without formal approval), duplicate payments to the same employee, and discrepancies between headcount records and payroll. Biometric attendance systems, though not essential, provide definitive records of who was present during the periods for which they claim payment.

Behavioral red flags in employees with financial access often precede detection of fraud. Warning signs include reluctance to take vacations or delegate tasks (employees committing fraud cannot afford to leave positions unattended), sudden lifestyle changes inconsistent with known income levels, defensive or evasive behavior when questioned about financial transactions, and unusual stress or irritability. While not definitive proof of misconduct, these behaviors warrant heightened scrutiny of that employee's financial activity.

Inventory and asset discrepancies are easier to detect in retail and manufacturing than in service businesses but remain important. Frequent stock shortages, systematic discrepancies between recorded inventory and physical counts, unauthorized access to storage areas, and unexplained asset disposals indicate potential theft.

Implementing red flag monitoring does not require sophisticated software or external experts. A manager reviewing transaction lists, bank statements, and payroll records monthly, asking critical questions about anomalies, and investigating unusual patterns provides effective detection. The key disciplines are consistency (making this a regular, scheduled activity) and independence (ensuring someone other than the transaction initiator conducts the review).

Practical Prevention Strategy #6: Cash Handling and Payment Controls

Cash is uniquely vulnerable to theft because it leaves minimal documentation. Even small daily losses—$20 or $50—compound into substantial fraud over months or years. For businesses handling significant cash volumes, specific controls are essential.

Dual-control requirements for cash handling mandate that at least two individuals be present when cash is counted, stored, or transferred. This makes it difficult for a single employee to skim cash undetected.

Regular and surprise cash counts verify that recorded cash matches actual amounts. Surprise counts are particularly effective: when employees know that cash will be counted monthly without advance warning, the temptation to "borrow" from the register knowing they can replace it before the count diminishes.

Detailed cash transaction logs documenting every cash receipt and disbursement, including time, amount, purpose, and initiating employee, create accountability and enable pattern analysis. Modern POS systems often automate this documentation.

Segregation of cash handling duties ensures that the employee receiving cash is not the employee depositing it, and that the employee counting cash is not the employee recording it in the accounting system. In very small businesses where this is impossible, compensating controls include having a manager deposit cash and verify deposit amounts against transaction records.

Practical Prevention Strategy #7: Vendor and Procurement Controls

Procurement represents a vulnerability point where external parties can influence employees to engage in corrupt practices. Kickbacks (where vendors provide payments to employees or managers in exchange for contract awards or favorable terms), billing fraud (where vendors submit inflated invoices), and collusion (where employees and vendors jointly defraud the company) are common procurement corruption schemes.

Vendor due diligence involves verifying the legitimacy of new vendors before engaging them and periodically reviewing relationships with existing vendors. A basic due diligence process includes business license verification, references from other companies, confirmation of physical business location, and tax identification number verification. This process prevents fraudsters from creating fictitious vendors through which to divert payments.

Segregation of procurement duties ensures that the employee selecting vendors is not the employee authorizing payments to those vendors, and that neither is the employee reconciling payments. In small organizations, compensating controls include requiring management approval of vendor selections and management review of vendor payments against purchase orders.

Approval thresholds for purchasing establish that purchases below a certain amount (e.g., under $500) require only a single manager approval, while larger purchases require two independent approvals or formal competitive bidding. This concentrates control over high-value spending where fraud risk is greatest.

Verification of vendor payment information changes prevents fraud where fraudsters redirect vendor payments to their personal accounts by submitting false payment information changes. Requiring documented authorization before processing any changes to vendor banking details or payment addresses provides protection.

Practical Prevention Strategy #8: Documentation and Accountability

Proper documentation is foundational to fraud prevention. Complete, accurate records enable both real-time management monitoring and post-fact investigation if fraud occurs. Documentation also deters fraud: fraudsters prefer environments where they can operate without leaving traces.

Requiring supporting documentation for all financial transactions—invoices, contracts, approval forms, delivery confirmations—creates a paper trail. Employees should be trained that transactions without complete documentation are not authorized for payment or recording.

Standardized approval forms ensure that transactions receive consistent oversight. A purchase order form, for example, should require vendor identification, description and quantity of goods/services, price, date, manager approval, and receipt confirmation before payment is authorized. Forms need not be complex—simple one-page templates suffice.

Signature requirements for high-value transactions or critical approvals provide documentation of who authorized specific actions. Even in organizations using electronic systems, manual signatures on periodic reviews provide evidence of management oversight.

Document retention policies ensure that records necessary for investigation and audit are preserved. Small businesses sometimes discard financial records after a period, compromising the ability to detect or investigate fraud discovered years later.

Addressing the "Few Employees" Challenge: Practical Solutions

The most common objection from small business owners is that prevention strategies designed for larger organizations are incompatible with organizations of five to ten employees. This is simultaneously true and irrelevant. The truth is that many prevention mechanisms designed for larger organizations are incompatible with small teams. The irrelevance is that plenty of proven strategies are specifically designed for resource-constrained environments.

The central principle is compensating controls: when traditional segregation of duties is impossible, replace it with alternative safeguards that achieve similar objectives. A business with three employees cannot segregate procurement, approval, and reconciliation—but the owner can personally approve all purchases and monthly reconcile a sample of payments against purchase orders. A business cannot have a separate audit department—but management can conduct monthly reviews of transaction categories. A business cannot maintain multiple layers of approval—but one person can require a second person's approval.

The key requirement is discipline and documentation. Prevention strategies fail not because the ideas are unsound but because implementation is haphazard. A manager resolves to review expenses monthly but only does so quarterly. An approval process is established but circumvented in urgent situations. A whistleblower hotline is installed but employees are never informed of its existence. Successful prevention requires commitment to consistent implementation.

Implementation: A Phased Approach

For a business owner deciding to implement corruption prevention measures, a phased approach is practical and sustainable.

Phase 1: Assessment and Documentation Identify the specific corruption risks relevant to the business. A retail business with cash register access faces different risks than a service business with large account receivables. A business with inventory faces different risks than one without. Document the critical financial processes—payment authorization, cash handling, expense reimbursement, inventory management—and identify where individual employees have excessive control. Create a simple segregation of duties matrix listing key transaction types and which employees have access to which steps. Identify gaps and design compensating controls.

Phase 2: Quick Wins Implement controls that require minimal cost and effort but deliver immediate impact. Establish a written anti-fraud and anti-corruption policy. Create a requirement that the owner monthly reviews and signs off on key financial reports or transaction categories. Institute surprise cash counts. Establish a hotline (cost: $29-100 per month) and communicate it to employees. These measures, implementable within 30 days, signal commitment to integrity and establish basic detective controls.

Phase 3: Sustainable Systems Implement ongoing monitoring and control processes designed to be sustainable with your staffing and budget. Establish quarterly internal audits of high-risk transaction categories. Conduct annual external audits (even if limited in scope). Implement training on fraud awareness. Establish a documentation standard for transaction approvals. Build these into regular management activities rather than treating them as one-time projects.

Phase 4: Continuous Improvement Periodically review the effectiveness of controls (quarterly or semi-annually). Adjust procedures based on what you learn. If cash discrepancies emerge despite controls, strengthen cash handling procedures. If vendor fraud occurs, tighten procurement processes. Corruption prevention is not a destination but an ongoing commitment to identifying weaknesses and addressing them.

The Cost Reality: Affordable Prevention vs. Expensive Recovery

The investment required for comprehensive corruption prevention in a small business is modest. A realistic budget for a small business with 10-20 employees implementing serious prevention measures might look like this:

- Whistleblower hotline: $500-800/year

- Annual external audit: $2,000-4,000/year

- Accounting software (if not already deployed): $50-150/month = $600-1,800/year

- Fraud awareness training: $0-500/year (can be internal)

- Background checks (ongoing for new hires): $100-200 per check

Total annual cost: approximately $3,500-7,500 for comprehensive prevention measures.

This investment seems substantial until compared against the reality of fraud in small organizations. The median fraud loss of $145,000 is not a hypothetical—it is the median, meaning half of detected fraud exceeds this amount. A business experiencing a single moderate fraud scheme over 18 months faces losses far exceeding the annual investment in prevention. For a business operating on typical profit margins, a fraud loss of $50,000 or more can consume the entire year's profit or trigger financial crisis.

Moreover, fraud detection is not certain in small organizations lacking formal controls. Fraud schemes in smaller entities often continue for years because detection is delayed. The typical fraud lasts 18-24 months before discovery, allowing fraudsters to accumulate losses that might have been detected and halted in months had effective controls been in place.

The mathematics are clear: prevention is dramatically less expensive than recovery.

Conclusion: Integrity as Competitive Advantage

Corruption prevention in small businesses is not about complicated policies or expensive systems—it is about disciplined commitment to integrity. The techniques outlined above—segregation of duties with compensating controls, regular audits, whistleblower hotlines, fraud awareness training, and systematic red flag monitoring—are proven, affordable, and implementable in any small organization.

The most significant barrier to prevention is not cost or complexity but rather the assumption that "we're too small for this to happen" or "everyone here is trustworthy." These assumptions are exactly what corrupt employees rely on. Formal controls, regular audits, and anonymous reporting mechanisms communicate that the organization is serious about integrity, deterring misconduct and ensuring that schemes are detected early when they emerge despite prevention efforts.

Small business owners who implement these measures gain an important competitive advantage: credibility and trust with customers, lenders, employees, and stakeholders. An organization known for integrity, with transparent controls and a culture that refuses to tolerate corruption, attracts better employees, retains customers, and commands respect in the marketplace. Conversely, fraud scandals damage reputations in ways that take years to remedy, if recovery is possible at all.

The investment in corruption prevention is thus not merely an expense but an investment in organizational integrity, financial health, and long-term sustainability. For resource-constrained small businesses, the strategies outlined in this article provide a practical roadmap to implementing controls that are affordable, implementable, and effective.